In the French department of Drôme, we find Saillans, a village of around 1,500 inhabitants that has been carrying out an innovative experience of local participatory democracy and community self-organisation, following the local elections of 2014, when a group of citizens jointly presented themselves to run the municipality and won.

The whole story started with a collective of citizens who were growing disenchanted with the way of ruling of the former Mayor. Once elected, the inhabitants of Saillans decided to reverse this top-down governance by putting citizens at the center of all debates and decision-making processes.

During the Western Caravan route in France, Jean Baptiste Marine, urban planner of the Saillans municipality, welcomed us a the Town Hall of Saillans, to tell us more about the way Saillans is run, with collegiality, transparency, and participation at its core.

Could you tell us more about the political and administrative system of Saillans and what makes it different from how other French towns are run?

Saillans is a village of 1,500 inhabitants and since 2014 we have been carrying out an innovative experience of local participatory democracy and community self-organisation, following the local elections of 2014, when a group of citizens jointly presented themselves to run the municipality.

After the elections, the current functioning and operational strategy and methods of local administration were set up based on three main pillars:

- Collegiality: This principle means that when it comes to local decisions, it is not the Mayor who makes all the decisions, but the whole municipal team together. We have a Mayor, Vincent Beillard, only because in France it is mandatory by law to have one. Each elected official has a field of specialisation, for example, environment, mobility or urban planning, on which he or she is responsible for. But they work in tandem with another elected from a different specialisation in order not to centralise skills.

- Transparency: The idea is to make all information accessible to any inhabitant. This was translated into tripling the number of information panels in Saillans, creating a website and a Facebook page, where all information and decisions are constantly updated. This means that we make the information of each municipal meeting accessible everywhere and publish very detailed reports on those meetings and share them online. The budget and salaries of the elected officials are also publicly announced. On top of this, we have also homogenised the salaries of the whole municipal team, they all earn the same, except the Mayor, because the French law requires it.

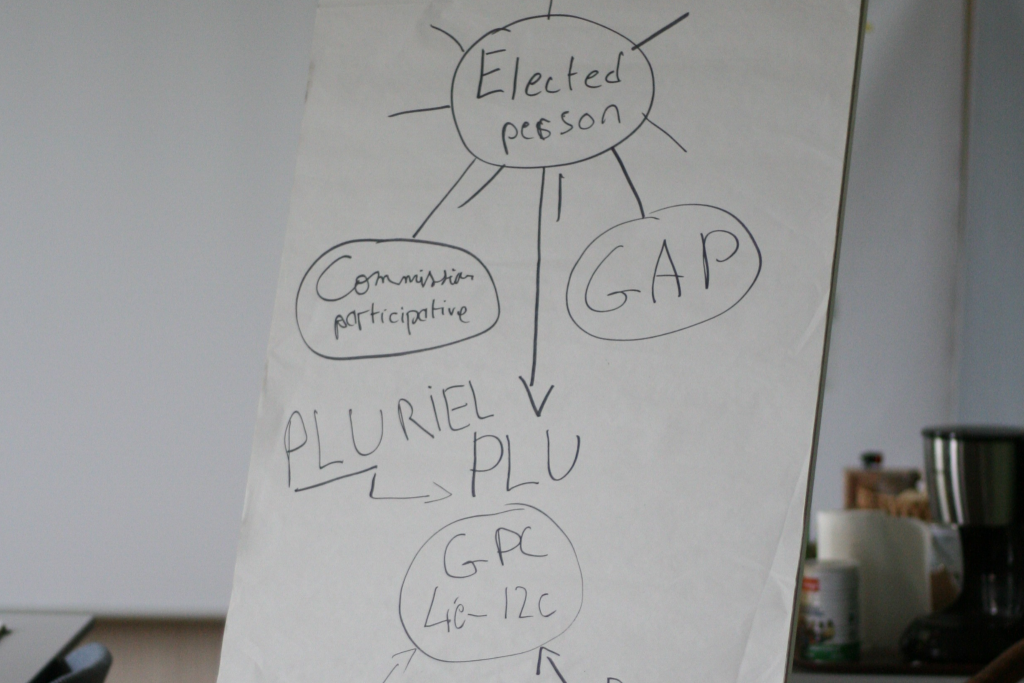

- Participation: Each major decision that is made, it is taken together with the inhabitants of Saillans. For every topic that has a relevant political stake, we hold public meetings and we propose the creation of a citizens’ commission to work on the subject. This participation principle is translated into two main entities: participatory commissions and GAPs (Action Project Groups). The first one, the participatory commissions, are commissions that meet once a year to define the village’s most important orientations and strategies on the seven main themes in which the elected representatives are divided. This meeting is open to everyone. The second, the GAPs, are composed of inhabitants who are responsible to together find ways of operationalising and making the proposals of the commissions concrete. For example, it was decided by the participatory commission on mobility to reduce the number of car parking spots in the village and to pedestrianise as much as possible. Therefore, the GAP decided to gradually reduce the number of parking spaces and to install parking relays outside the village in order to free the center from cars.

“It is not the Mayor who makes all the decisions, but the whole municipal team together.”

Saillans has not always been ruled in this way, only since 2014. How did it all start?

Indeed, it has been only since 2014 that we have been implementing this system. Before that, the situation was very different: there was a Mayor who has mostly taken decisions, only with the help of a few advisers. The citizens saw this as normal because it is like this in most cities in France. But he did a big mistake with a project: he wanted to build a supermarket just outside the entrance of Saillans. Considering the small size of the village, the inhabitants believed that the supermarket would destroy all the local commerce of the center, so there was a strong mobilisation against this project and the citizens managed to prevent this supermarket from being built.

This victory made the inhabitants of Saillans reflect on a major question: “Are we willing to have municipal management where the Mayor is taking all the decisions and we complain if the decision is not good to us? What can we do differently in Saillans?” That is how a group of citizens, a mix of young and old people, concerned about acting directly for their city presented themselves as a list for the mayorship of the village. They won the elections and paved the way for the current type of municipal governance.

If we focus on the participation pillar, what flagship project would you highlight as a very successful case?

One of the most successful examples when it comes to citizens’ participation was the creation of the new local plan of urbanism. Normally, these are very controversial proposals, because you might need to remove buildings, lands or parking spots or promote densification, which are tricky and life-changing issues for the population.

We held around 25 public meetings in order for this plan to be put forward and I consider those meetings were one of our biggest victories. The aim of those encounters was to listen to the population and find out what they had to say about this new urban planning proposal. The outcome of those meetings was sent to the GPC (Groupe de Pilotage Citoyen or Citizens’ Managing Group), who were responsible to collectively set the strategies of the land-use plan. This Citizens’ Managing Group is made up of a total of 16 people, one third are elected representatives and two thirds are inhabitants randomly selected.

Thanks to this long collective process, I think this urban plan will be much more accepted than it is in other municipalities in France. By involving the citizens in the process, they were able to understand some of the controversial decisions that needed to be taken.

“We make the information of each municipal meeting accessible everywhere and publish very detailed reports on those meetings and share them online.”

What are the challenges of having such a participatory system?

The first challenge I would point out is the amount of time you need to decide collectively. For all the decisions, we go for three steps: first, we aim for consensus -meaning, everybody agrees-, if it fails, then we aim for consent -nobody opposes-, and if it is still not possible, then we have to vote on it. So for example, when we were discussing the new local urban plan I was mentioning before, sometimes we didn’t have the time to go through these three steps and then we had to go straight to voting. That can be problematic because when you use voting, you can easily create divergent groups, such as old people vs young people or traditional people VS ecologists, and that can harm the unity of our community. I regret not being able to respect some of our initial ambitions and that we could not always follow the collegial and intelligent way of deciding.

“By involving the citizens in the process, they were able to understand some of the controversial decisions that needed to be taken.”

A second challenge I would mention is the energy that the organisers have to put behind such administrative and political processes. We have had cases of some elected officials quitting and some others being close to burning out because of the amount of time and dedication that this system requires to be functional. When you think of participatory democracy, it is interesting to realise that one could think that the more you involve people, the fewer things you have to do, and it ends up being quite the opposite.

These are some of the reflections we have for the next local elections coming up in 2020. We are wondering: “How can we have a more bearable system for those who are truly committed for it to work?”

Interview with: Jean-Baptiste Marine, Urban Planner of the Saillans municipality with Adriana Díaz Martín-Zamorano.